Resources

Search below for resources covering the intersection of climate engagement, social science and data analytics.

RESULTS

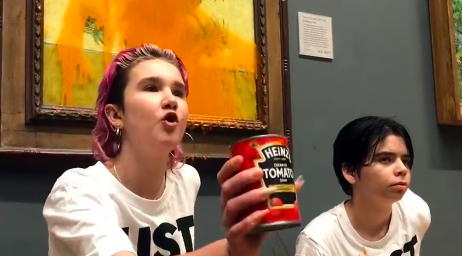

The method behind Just Stop Oil’s madness

The climate group that threw soup on a Van Gogh knows they annoy you, but that might be part of why their controversial approach works. Contrary to many of these criticisms, there is also a large body of academic literature arguing that radical activism could be beneficial for the environmental movement as a whole. More recently, several polls and surveys have shown that the use of disruptive radical tactics can increase awareness of key issues and generate support for more moderate groups in the same movement. Other studies show that radical tactics are effective when they are contrasted with a set of moderate demands that the government can easily adopt. This article interviewed 12 members from around the U.K., asking how radical flank effects function when applied outside the ivory tower of academia.

Reflections: What Went Wrong with the Sunrise Movement

The Sunrise Movement has had successes but also experienced internal difficulties. This article, a personal reflection on Sunrise experience, argues that the energy and mobilization of the 2018-2020 years that led to a surge of youth joining the Sunrise Movement won’t be possible in the next four years unless a new organizational strategy is built in the youth climate left. This author organized with a local Sunrise “hub” and then joined national leadership teams. However, Sunrise internal politics were based on who you knew.

The Tomato Soup “Controversy”

The climate movement is getting more confrontational—is it working? In October 2022, activists with the group Just Stop Oil in the UK threw tomato soup at Van Gogh’s famous painting, “The Sunflowers,” in the National Gallery in London, then glued themselves to the wall under the painting, asking onlookers “What is worth more, art or life?” Within 24 hours most major media outlets had covered the protest in some way. Many covered it multiple times over the course of several weeks. It also inspired multiple copycat actions, with activists throwing mashed potatoes on a Monet in Germany, and pea soup on another Van Gogh in Italy. While the reaction to “Soupgate” seemed over the top, it’s also not terribly surprising that people were upset by it, because shock was the point, according to Dana Fisher, a sociologist. Part of the point of what researchers call the “radical flank” of any movement is to get this sort of reaction.

How climate activists won the American Climate Corps

Last month, President Joe Biden announced the launch of the American Climate Corps, or ACC — a program that will train some 20,000 young people in careers in climate and clean energy. In this resource, Sunrise Movement co-founder Evan Weber discusses the years of Green New Deal organizing that led to the landmark new jobs program to address the climate crisis. A broad paint brush of tactics contributed to the win that is the American Climate Corps. These tactics included 500 young people getting arrested for blocking the White House in the summer of 2021 while demanding a fully-funded civilian climate corps in the Build Back Better negotiations. They also included behind-the-scenes lobbying and policy negotiation, coalition building and the electoral work that delivered some of the highest youth voter turnout in modern history — with climate being the reason that happened. The latter is also the reason President Biden went more aggressive on climate and updated his climate policy.

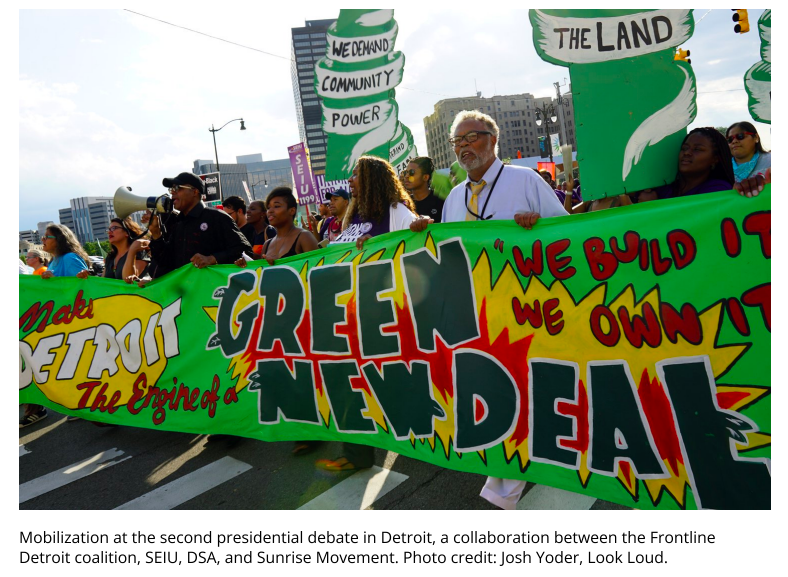

Blueprint for a Multiracial, Cross-Class Climate Movement: The Report on Coalitions

Multiracial, cross-class (MRXC) coalition-building is essential if the climate movement is serious about tackling the climate crisis at the scale it demands. However, a historical lack of collaboration, trust, or healthy mechanisms to deal with conflict often impair those efforts. This Blueprint report and accompanying workbook provide an analysis of the difficulties MRXC climate coalitions are likely to face and offer recommendations for a proposed path forward.

Blueprint for a Multiracial, Cross-Class Climate Movement: The Workbook for Coalitions

This workbook is meant to help you translate the analysis and recommendations we provide there into workable features of your organizing. Whether you’re currently involved in a multiracial, cross-class climate coalition, thinking about starting one, or evaluating a past coalition on reflection, we hope this workbook clarifies for you and your coalition partners the breadth of considerations and decisions you should be prepared for.

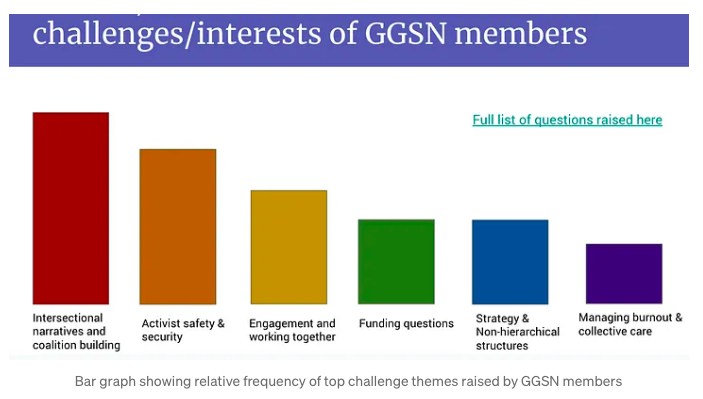

The emerging picture of the most-often cited challenges grassroots groups are facing currently includes: 1) Help with building intersectional narratives and coalitions to link struggles together; 2) Activist safety & security in repressive environments; 3) Maintaining activist engagement and working together efficiently in groups; 4) How to secure funding for grassroots organizing and how to report impact; 5) How to build effective strategy within non-hierarchical structures; 6) Managing burnout among activist communities & collective care. The Global Grassroots Support Network is a collection of 84 seasoned grassroots organizers, campaigners, coaches and more. The Network supports struggles for climate justice, reproductive justice, LGBTQIAS+ rights, housing justice and workers’ rights. These members currently come from: Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Kenya, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Spain, Tanzania, Turkey, Uganda, the U.S., UK and Zimbabwe. If you’re excited by the mission of supporting grassroots justice-oriented activists, the Network has lots of room for new members and you can commit the amount of time that is accessible to you, and the input that supports your mission.

The Kernel: A Tool for Developing Good Strategy (and Avoiding Bad Strategy)

The Sunrise Movement successfully relied on the “strategy kernel for campaigning.” The kernel involves three elements: a diagnosis that defines or explains the nature of the challenge, a guiding policy for dealing with the challenge, and a set of coherent actions that are designed to carry out the guiding policy. The Sunrise Movement used the kernel by convening the leadership team for a meeting to discuss each layer of the kernel; usually, a small team then took responsibility for completing the kernel, providing overarching direction for our shared work. In strategy work for movements, this resource’s author has been part of many conversations that began instead with deliberating the third layer of the kernel—the actions the group should take—and ended up spiraling into disagreement. The #ChangeTheDebate campaign in the spring and summer of 2019 is an example of how Sunrise used the kernel: Diagnosis—a central challenge is that the Green New Deal (GND) is polarized and presidential candidates are not talking about it because of the strategic narrative attacks from Fox/right-wing media; Guiding Policy—the movement must force presidential candidates to publicly and boldly talk about the GND in the media; Coherent Actions—launch the campaign will compelling visuals, host debate watch parties across the movement, catalyze a centralized mass action, birddog Biden and other candidates, and run a targeted, escalated action demanding time during the debate devoted to climate.

On the declining relevance of digital petitions

Digital petitions are a mostly-outdated tactic now. Both our politics and our media environment have moved in directions that render them less useful. Where petitioning used to be the central tactic in a digital campaigner’s toolbox, the Trump years saw a rebirth of collective, place-based mobilization. They were years of record-setting marches and participatory local-level civic engagement. Plus we’ve seen a renaissance in union organizing these past few years. But still, the relevance of petitions has diminished—related to the pervasive sense that government officials no longer behave as though listening to and representing citizens is a core part of the job. And it’s a reminder that most of our digital behavior is downstream of a small handful of quasi-monopolistic companies. If American Democracy is going to make it through the next decade, we are going to need better elites. I suspect, if that happens, we will happen to see digital petitions make a comeback. In the meantime, campaigners will do the best with the tools they have available—they’ll develop tactical repertoires that fit the changing media environment and respond to the political opportunity structure.

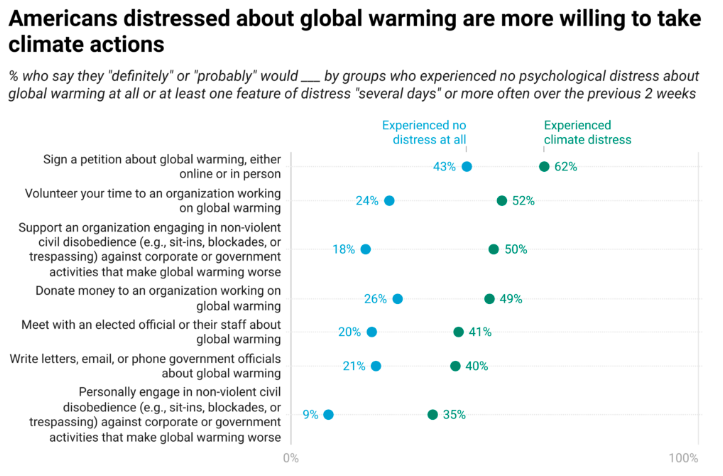

Is distress about climate change associated with climate action?

Americans who experience climate distress are more likely to take personal action on climate change. Americans who had experienced at least one feature of climate distress were much more likely than those who had not to say they had taken different forms of climate action. This includes having signed a petition about global warming (46% vs. 10%, respectively), or having volunteered at an organization working on global warming (19% vs. 2%). Americans who experienced at least one feature of climate distress were more likely than those who had not to say they would meet with an elected official or their staff about global warming (41% vs. 20%, respectively), write letters, email, or phone government officials about global warming (40% vs. 21%), or personally engage in non-violent civil disobedience (e.g., sit-ins, blockades, or trespassing) against corporate or government activities that make global warming worse (35% vs. 9%).

Pagination

- Previous page

- Page 2

- Next page